The Great Year and Its Twelve Houses

Posted in insights on July 7, 2023 by Zara Zinsfuss ‐ 28 min read

The Great Year

Whenever we want to understand our place in the universe, we gaze into the deep night sky, losing ourselves in the myriad of stars within our sight. It seems that the cosmic activities unfolding above us make up a grand narrative, of which we, the inhabitants of planet Earth, are merely a subscene.

Thus, it’s natural for any Earthly dweller to initiate inquiries about their location and significance in relation to the vast expanse of space and time.

Our celestial understanding begins with acknowledging the three key motions of our planet Earth:

- Rotation around its axis

- Revolution around the Sun

- Precession of its axis

The first two motions are intrinsically part of our daily life as we experience their effects in tangible ways. However, the third motion, which will be our primary focus, is less remembered despite its significance. All three motions exhibit recurrent patterns, repeating over time, forming cycles each with a specific duration or period.

| Earthly Motion | Period (approx.) | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Rotation | 24 [h] | Day / Night |

| (2) Revolution | 365 [d] | Year |

| (3) Precession | 26'000 [y] | Great Year |

The day-night cycle (1) is a result of the Earth’s rotation and impacts life significantly. For practical purposes, we divide a day into two equal segments of 12 hours, aligning with the Circadian rhythm that regulates wakefulness and sleep for many mammals, including humans.

The second cycle, the year (2), is observable through the changing seasons of spring, summer, autumn, and winter, especially in higher and lower latitudes. We typically divide the solar year into twelve parts, or months, each approximately 30.5 days long.

The lunar cycle, though not covered in detail here, is interesting to note. It occurs almost precisely 13 times in a year, with each lunar month lasting slightly over 28 days. This divergence between lunar and solar years leads to interesting questions regarding our calendar system.

The third cycle, lesser-known yet equally significant, is the Earth’s axial precession or precession of the equinoxes. Known also as the Great Year (3), it takes between 25,772 and 25,920 years to complete a full cycle.

Precession is a complex motion, difficult to describe without visual aids. For context, to show that we’re not making this up, let’s look at Merriam-Webster and how they define it the notion of precession:

a comparatively slow gyration of the rotation axis of a spinning body about another line intersecting it so as to describe a cone1

In the case of planets such as Earth, one needs to specify that ones means the so-called precession of the equinoxes. Britannica defines the precession of the equinoxes as follows:

… motion of the equinoxes along the ecliptic (the plane of Earth’s orbit) caused by the cyclic precession of Earth’s axis of rotation.2

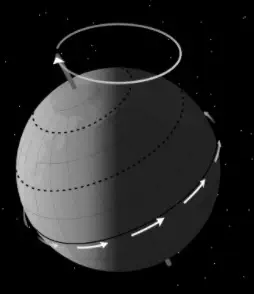

The following figure elucidates axial precession, depicting the Earth’s rotation axis gyrating in a circular pattern:

The direction of precession (circular arrow at the top) counteracts the Earth’s rotational spin (circular arrows around the globe). These conflicting rotations produce a peculiar dance in our heavens. For an Earth-bound observer, this means the daily dance of the sky against the constellations counterpoints the slow waltz due to precession across its 25,920-year cycle.

The implications of this precession are immense and serve as the bedrock of our understanding of time and astrological ages. As we journey through the Great Year, the backdrop of the stars shifts gradually. This cosmic shift, though imperceptible within a human lifespan, has profound implications over thousands of years.

In the next section, we’ll delve deeper into these ramifications, unravelling the astrological epochs that punctuate our celestial journey through the Great Year and their impact on our sociocultural evolution.

The Twelve Houses

With the understanding of the three key motions of the Earth, we recognize that these celestial rhythms provide an intricate frame of reference that enables us to conceptualize and measure time. These cyclical motions share several intriguing characteristics:

- Definitive periodicity: These motions, untouched by human intervention, depict a recurrent cosmic choreography, repeating the same patterns in a rhythmic cycle that is bound to start again once completed.

- Consistency of time elapse: Because of this inherent periodicity, we can expect the exact same amount of time to elapse for a given cycle. This offers a degree of predictability and reliability unmatched by human-made systems.

- Granularity: The natural segmentation of a full cycle provides smaller, discrete units of time, enabling us to perceive time in digestible bites, rather than overwhelming, continuous stretches.

These harmonious cosmic rhythms hold a profound sense of mystery and grandeur that exceeds our typical human scale of perception. Thus, using these celestial motions as a time-keeping framework becomes intuitively appealing, particularly because all three motions exhibit intervals that complement each other extraordinarily well.

The day, a product of the Earth’s rotation, becomes a manageable unit to count a year, which in turn, stemming from the Earth’s revolution, offers a feasible measure to gauge the enormity of the Great Year, a result of precession.

This interlocking of time scales gives rise to an intriguing pattern: the division of the rotation and revolution cycles into 12 units each. This division, while seemingly arbitrary, has far-reaching implications when applied to the precession cycle or the Great Year.

Dividing the Great Year by twelve gives birth to a new time unit: the Great Month, each spanning a staggering 2,160 years. This unit embodies a vast stretch of time, dwarfing our conventional year and providing a measure for time spans that cross the threshold of millennia.

The concept of the Great Month offers a larger temporal framework that encompasses the rise and fall of civilizations, the evolution of cultures and ideas, and the progress of scientific understanding. It gives us a perspective on time that goes beyond our personal or even historical experience, reaching into a scale that we usually reserve for geological or astronomical events.

Just as the daily and annual cycles are integral to our understanding of time, the Great Month could prove to be an essential tool for understanding longer-term trends and cycles. As our knowledge of our own (ancient) history, the constitution of planet Earth, and astronomical patterns continues to grow, we may find that the concept of the Great Month helps us make sense of patterns and events that span thousands of years, providing a broader context for understanding our place in the cosmos.

This broader framework of time, provided by the twelve houses of the Great Year, each a Great Month, enables us to comprehend vast stretches of time that would otherwise seem incomprehensible. It is a cosmic calendar that places our transient existence into a grand chronicle of the universe.

Mapping the heavens into constellations

As we continue our cosmic voyage, let’s pause to consider the age-old human practice of Earthly stargazing and the crucial role it has played in our understanding of the universe. As highlighted in the introduction, humans across cultures and epochs have turned their gaze upwards to the celestial theater, seeking to comprehend their position amidst the glittering array of heavenly bodies. This shared fascination transcends cultures, continents, and millennia, connecting us with our ancestors in a shared quest to unravel the mysteries of the universe.

Early humans not only marveled at the stars but came up with an ingenious solution to navigate this overwhelming cosmic map: grouping the multitude of visible stars into meaningful clusters known as constellations. This form of early science was not only practical but ingeniously symbolic, layering each cluster with a mythological tale. Through these storied shapes, abstract cosmic data took on a narrative quality, anchoring spatial patterns in the memorable tales of gods, monsters, and heroes. The storytelling aspect is arguably as crucial as the spatial one; it facilitated knowledge transmission across generations, allowing the wisdom of the past to enlighten the present.

Armed with the ability to recognize these celestial patterns, humans could discern practical, actionable information, such as the timing of agricultural activities or navigation for long sea voyages. The constellations became our cosmic compass, guiding our way through the seasons and across vast bodies of water.

Yet, the stellar canvas is not static. As we just learned a few paragraphs earlier, the gradual progression of axial precession, despite its subtle nature, inexorably reshapes the constellations’ arrangement in the night sky. This slow celestial dance, overlooked by casual observers, becomes apparent to those invested in careful, long-term celestial tracking. With axial precession taking approximately 25'920 years for a full cycle, a shift of 1° on the celestial sphere equates to a time span of 72 years, roughly aligning with an average human lifetime. Remarkably, this 1° shift is also closely proportional to the combined apparent diameter of the Sun and the Moon in our sky.

Such findings underscore the sheer complexity of observing and comprehending axial precession. Without efficient means for inter-generational persistence of empirical knowledge, the task becomes even more daunting. Yet, humanity’s enduring curiosity and capacity for pattern recognition have allowed us to pierce this cosmic mystery, using nothing more than our naked eyes and the night sky as a canvas for our stories and mathematical explorations.

Marking Time: The Importance of Cardinal Days in a Year

Before we continue our cosmic journey, it’s crucial to focus on another distinctive aspect of Earth’s annual journey around the Sun, influenced by the planet’s axial tilt of 23.44° in relation to its orbital plane. This tilt not only gives our planet its characteristic seasonal rhythm but also impacts how we perceive the Sun’s light throughout the year.

Let’s delve a bit deeper into these astronomical concepts. The celestial equator is the projection of the Earth’s equator onto the sky, while the ecliptic is the apparent path the Sun traces in this celestial sphere due to Earth’s revolution. The celestial equator and ecliptic intersect twice a year at two specific points, marking the spring and autumnal equinoxes. These equinoxes signify the moment when the duration of day and night is equal across the globe. The spring equinox (also known as the vernal equinox) typically occurs on the 20th of March, and the autumnal equinox around the 22nd of September.

Conversely, the summer and winter solstices denote the moments when one hemisphere of the Earth experiences the longest day or longest night of the year, respectively. The summer solstice generally falls on the 21st of June, while the winter solstice occurs around the 21st of December.

These equinoxes and solstices - the cardinal days - are considered pivotal astronomical milestones in our calendar, marking the start of each season.

| Cardinality | Day in a year | Perceptibility |

|---|---|---|

| Vernal equinox | ~ 20th of March | Day and night of equal length |

| Summer solstice | ~ 21st of June | Longest day in the Northern Hemisphere |

| Autumn equinox | ~ 22nd of September | Day and night of equal length |

| Winter solstice | ~ 21st of December | Longest night in the Northern Hemisphere |

Bear in mind that an equinox or solstice represents a specific moment in time when the celestial equator aligns with the ecliptic, not an entire day. Another way to define an equinox is the moment when the visible Sun’s center is directly over the Earth’s equator.

Viewing Earth as a grand celestial clockwork, the cardinal days can be seen as markers for the four quadrants on a clock face. In essence, if we were to pick a moment to compare celestial measurements, the cardinal days, particularly the equinoxes, would be the most desirable due to their globally observable characteristics.

Astronomical watchmaking

Navigating the intricate choreography of Earth’s three key motions - two of which present a rapid periodicity - is a demanding task, particularly when trying to discern the glacial pace of the third motion, the precession. Its slow, stately progression requires the observer to select a specific moment each year for stellar observation, akin to the interplay of distinct mechanisms within a mechanical wristwatch that work in harmony to accurately portray time. Just as a wristwatch employs a time reference, typically 0 or 12 o'clock, the Great Year also calls for a defining point of reference.

To construct our model of an astronomical timepiece, we need to consider specific reference points, namely:

- First motion [rotation]: Sunrise, which heralds the start of a new day

- Second motion [revolution]: Spring Equinox, marking the arrival of a new cycle of seasons

- Geographical point of reference: Due East, the direction from which the Sun makes its daily ascent

By leveraging these sensible parameters to establish our ‘zero’ point, we can now observe the celestial tapestry – the stars or constellations – unfolding against the backdrop of the Great Year.

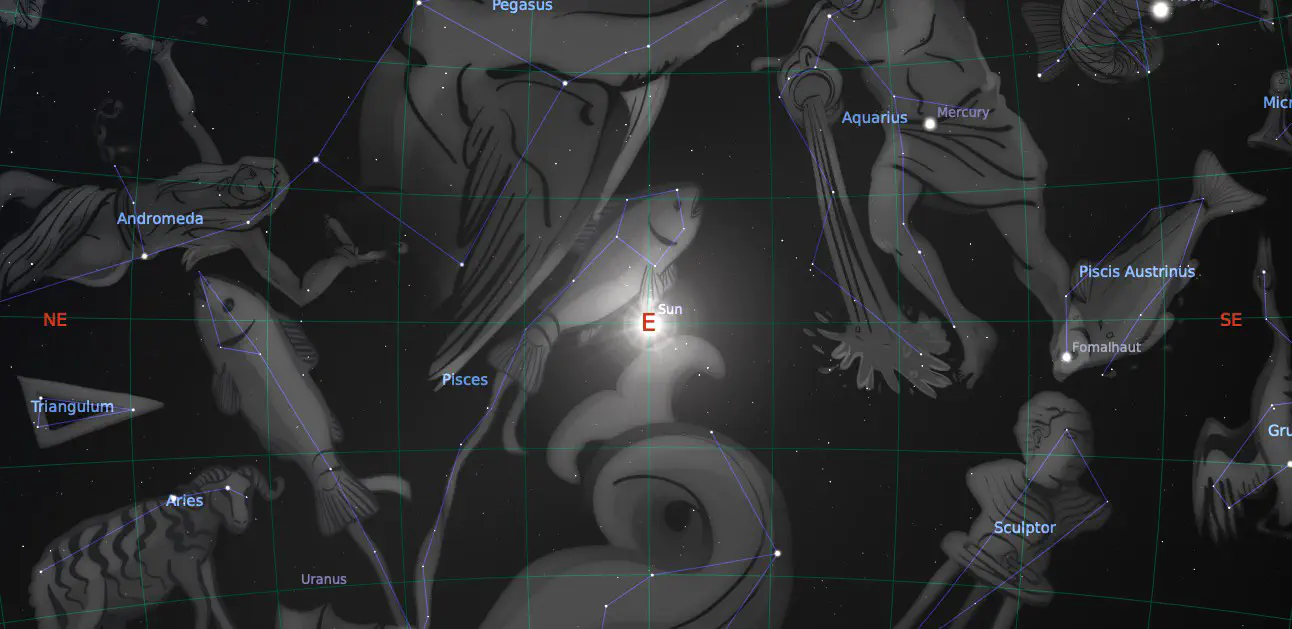

One might then wonder, what constellation graces the pre-dawn sky on the spring equinox, rising in unison with the Sun due east, in our current era?

As we look to the heavens, we find ourselves at the threshold of a cosmic shift, where the constellation of Pisces is giving way to the upcoming constellation of Aquarius. This celestial transition silently marks the passage of millennia, a grand celestial clock advancing into a new age. This is the precise moment where the ancient and the current converge, providing us with an invaluable glimpse into the cosmic shift into a new age. A new age that could have been easily predicted for millenia if the awareness and knowledge about axial precession were given.

The Cycle of Zodiacal Ages

Our prior assumptions about celestial observations and their correlation with the slow progression of the precession of the equinoxes were not arbitrary. This understanding is deeply rooted in antiquity. This exploration propounds that the Zodiac’s genesis is intrinsically linked to precession. The term Zodiac refers to a group of 12 constellations, whose mention transcends written history and cultural boundaries. Undeniably, the Zodiac and its derivative study, now known as astrology, have been of significance for thousands of years.

The oldest known civilization, the Sumerians, had profound respect and knowledge of the Zodiac. Linking the precession to the Zodiac is controversial, as it implies comprehensive understanding of the former, requiring considerable scientific knowledge including the concept of Earth as a globe. To attribute such cosmological insights to the earliest known civilization would challenge the contemporary consensus on known history, casting doubt on the linear and gradual narrative of human progress. Such a perspective could provide a basis for alternative narratives.

Returning to the Zodiac, the term originates from Ancient Greek zōidiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακός κύκλος) meaning _‘cycle or circle of carved animals’3. However, in non-Indo-European languages, the Zodiac has different names. In Biblical Hebrew, the Zodiac is called Mazzaroth (מַזָּרוֹת), translating to ‘garland of crowns’↩︎. The phrase ‘mazel tov’ (מזל טוב), wishing good luck or more accurately good fortune, derives from mazzaroth. In Chinese logograms, the Zodiac is referred to as 獣帯, meaning ‘animal belt’.

The Zodiac comprises 12 constellations, twelve signs. These twelve constellations are part of the ecliptic. This is no mere coincidence, as it is precisely the ecliptic which aligns with the celestial equator on the equinoxes (refer Cardinal days in a year and their importance).

If following the ecliptic on the equinoxes is indeed the correct method to track the precession’s progression, the Great Year, then the twelve constellations positioned along the ecliptic indeed represent the twelve houses or the twelve Great Months for a given Great Year. As we’ve established earlier, dividing the Great Year into twelve houses makes each house last 2'160 years.

One might wonder whether we have already transitioned into the Age of Aquarius or are still in the Age of Pisces. To answer this, one must first understand when the precessional cycle initially began, or more specifically, when a given house precisely begins or ends. Unfortunately, this isn’t easy to determine without significant assumptions. However, it is clear that as we progress through the early 21st century, the possibility of being in the new Age of Aquarius increases.

Aquarius is both a constellation and the twelfth of a circle known as a sign. Entering Aquarius means entering the period during which astronomers will see the sun rise in Aquarius on the day of the vernal equinox. The phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes is involved in this fact. The equinoctial sun has been rising in the sign of Aquarius since 1950. In this interpretation, we are in the ‘Golden Age’ of prophecies. The equinoctial sun will not begin rising in the constellation of Aquarius until about the year 2700. In this interpretation, neither you nor I will see the prophesied ‘Golden Age’.

– Jean Sendy: Coming Of The Gods (1970), p. 69

The duration of a house could also be determined by the size of a given constellation in the sky. However, this would be a poorly defined assumption as the shapes of Zodiacal constellations vary greatly. Pisces, for instance, has a considerably large constellation, particularly in ecliptic length, whereas Aquarius is comparably short. There is a significant gap between these two constellations. It’s important to note that the duration of a Great Month is 2'160 years, mimicking the twelfth section of its parent year cycle. For reasons that may be highlighted in future discussions, the year 1'950 AD as the beginning of the Age of Aquarius appears to be our best assumption for now.

Based on these assumptions, calculating the Zodiacal Ages backward by decrements of 2'160 years, we arrive at the following table:

| Zodiacal age | Time span``` | |

|---|---|---|

| ♑ Capricorn | 21'810 – 19'650 BC | Sea goat, Mountain Goat |

| ♐ Sagittarius | 19'650 – 17'490 BC | Archer, Centaur |

| ♏ Scorpio | 17'490 – 15'330 BC | Eagle, Phoenix |

| ♎ Libra | 15'330 – 13'170 BC | Scales, Balance |

| ♍ Virgo | 13'170 – 11'010 BC | Virgin, Grain Goddess |

| ♌ Leo | 11'010 – 8'850 BC | Lion, Nemean Lion |

| ♋ Cancer | 8'850 – 6'690 BC | Crab, Scarab, Turtle |

| ♊ Gemini | 6'690 – 4'530 BC | Twins, Dioscuri |

| ♉ Taurus | 4'530 – 2'370 BC | Bull, Calf, Bison |

| ♈ Aries | 2'370 – 210 BC | Ram, Golden Fleece |

| ♓ Pisces | 210 BC – 1'950 AD | Fishes, Twin Fish |

| ♒ Aquarius | 1'950 AD – 4'110 AD | Water Bearer, Fountain |

These denote the World Ages of the past. Looking into the future, after Aquarius comes Capricorn, followed by Sagittarius, and so on. The relevance of these ages extends beyond simply knowing the hour of a day, the day of a year, or the age of ages. Understanding precession and tracking it through ecliptic constellations allows us to position ourselves within larger timescales. It is a conventional way of referring to vast time spans surpassing mere years. If there’s anything worthy of measuring World Ages, employing the Earth’s third key motion, enabling millennia-long time references, is surely the most intelligent approach.

If our Earth’s inhabitants employed this understanding in the past, could we now comprehend what they might have meant when referring to world ages or aeons of time?

Encoding

Past civilizations have not only known about the precession of the equinox, but they have also endeavored to preserve this sacred knowledge. This preservation occurred in two notable forms: language and constructions. Both these forms served as mechanisms of encoding that have carried this ancient wisdom through ages, allowing it to transcend the ravages of time and cultural shifts.

Hamlet’s Mill

In 1969, a groundbreaking work was published that would provide an intricate insight into the encoded understanding of the precession of the equinoxes. This knowledge, the authors proposed, had its roots in an ancestral civilization characterized by a highly sophisticated understanding of the cosmos. This civilization, they claimed, had transmitted this knowledge through subsequent world civilizations, encoded within the rich tapestry of mythical images and narratives.

This remarkable study was conducted by Giorgio de Santillana (1902–1974), a professor of history of science at the esteemed Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Hertha von Dechend (1915–2001), a professor of history of science, philosophy, and ethnology at the University of Frankfurt. Together they co-authored Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and Its Transmission Through Myth.

Their book offers a revolutionary perspective, emphasizing the holistic and interconnected nature of archaic thought, and the profound role the celestial dynamics played in shaping their worldview. Let’s allow their words to elucidate:

“To begin with, there is no system that can be presented in modern analytical terms. There is no key, and there are no principles from which a presentation can be deduced. The structure comes from a time when there was no such thing as a system in our sense, and it would be unfair to search for one. There could hardly have been one among people who committed all their ideas to memory. It can be considered a pure structure of numbers. From the beginning, we considered calling this essay ‘Art of the Fugue.’ And that excludes any ‘world-picture,’ a point that cannot be stressed strongly enough. Any effort to use a diagram is bound to lead into contradiction. It is a matter of times and rhythm.”

“The subject has the nature of a hologram, something that has to be present as a whole to the mind. Archaic thought is cosmological first and last; it faces the gravest implications of a cosmos in ways which reverberate in later classic philosophy. The chief implication is a profound awareness that the fabric of the cosmos is not only determined, but overdetermined and in a way that does not permit the simple location of any of its agents, whether simple magic or astrology, forces, gods, numbers, planetary powers, Platonic Forms, Aristotelian Essences or Stoic Substances. Physical reality here cannot be analytical in the Cartesian sense; it cannot be reduced to concreteness even if misplaced. Being is change, motion, and rhythm, the irresistible circle of time, the incidence of the ‘right moment’, as determined by the skies.”

– Giorgio de Santillana, Hertha von Dechend: Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and Its Transmission Through Myth (1969), p.56

Santillana and von Dechend challenge the modern perception of precession as a trivial celestial motion and invoke the grand vision our ancestors had towards this cycle. They argue that the precession, for our forebears, represented a majestic secular motion — a peg on which they hung their profound thoughts about cosmic time:

“We today are aware of the Precession as the gentle tilting of our globe, an irrelevant one at that. As the GI said, lost in the depth of jungle misery, when his friends took refuge in their daydreams: ‘When I close my eyes, I see only a mule’s behind. Also when I don’t.’ This is, as it were, today’s vision of reality. Today, the Precession is a well-established fact. The space-time continuum does not affect it. It is by now only a boring complication. It has lost relevance for our affairs, whereas once it was the only majestic secular motion that our ancestors could keep in mind when they looked for a great cycle which could affect humanity as a whole. But then our ancestors were astronomers and astrologers. They believed that the sliding of the sun along the equinoctial point affected the frame of the cosmos and determined a succession of world-ages under different zodiacal signs. They had found a large peg on which to hang their thoughts about cosmic time, which brought all things in fateful order. Today, that order has lapsed, like the idea of the cosmos itself. There is only history, which has been felicitously defined as ‘one damn thing after another.’”

– Giorgio de Santillana, Hertha von Dechend: Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and Its Transmission Through Myth (1969), p.67-68

The authors take a step further to explore the fundamental divide between archaic and modern ways of interpreting the cosmos. They argue that the key to understanding archaic thought is through astrology, a cosmic language that encapsulated their profound sense of correspondences and deterministic principles:

“The greatest gap between archaic thinking and modern thinking is in the use of astrology. By this is not meant the common or judicial astrology which has become once again a fad and a fashion among the ignorant public, an escape from official science, and for the vulgar another kind of black art of vast prestige but with principles equally uncomprehended. It is necessary to go back to archaic times, to a universe totally unsuspecting of our science and of the experimental method on which it is founded, unaware of the awful art of separation which distinguishes the verifiable from the unverifiable. This was a time, rich in another knowledge which was later lost, that searched for other principles. It gave the lingua franca of the past. Its knowledge was of cosmic correspondences, which found their proof and seal of truth in a specific determinism, nay overdeterminism, subject to forces completely without locality.”

– Giorgio de Santillana, Hertha von Dechend: Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and Its Transmission Through Myth (1969), p.74

The Language of Mythology

The authors posited that mythology, often overlooked as mere fanciful stories, served as a complex and subtle medium for encoding this ancient wisdom. These tales, spun with cryptic symbolism, were carefully woven tapestries hiding a coded language that mirrored the cosmos’ movements and cycles. This language, unlike our contemporary scientific language, expressed relationships, patterns, and correspondences rather than explicit cause-and-effect relationships.

The second form of preservation, constructions, refers to the architectural marvels of the past, whose sophistication and precision in alignment with celestial bodies still bewilder modern researchers. These constructions - from the Pyramids of Giza to Stonehenge, and from the Mayan temples to the complex layout of Angkor Wat - all reflect an acute understanding of celestial mechanics and a desire to embody these cosmic rhythms in earthly form. They stand as colossal markers of a civilization's understanding of the cosmos, aligning earthly and heavenly cycles into a harmonious, integrated whole.

The legacy of these ancient civilizations and their profound cosmic understanding continues to whisper its wisdom to us, hidden in the language of myth and the stones of ancient constructions. As we decode these messages and comprehend their significance, we might re-discover a worldview that paints a more connected, harmonious, and rhythmically flowing cosmos, echoing the complex symphony of the precession of the equinox. This understanding may invite us to reconsider our place in the cosmos, not as detached observers, but as participants in a grand, cyclic dance of celestial bodies and cosmic time.

Zodiacal Constructions as Time Markers

Archaeoastronomy, the study of how past civilizations understood phenomena in the sky and how they utilized this knowledge in their cultures, is a captivating blend of anthropology, astronomy, history, and archaeology. This discipline’s foundation can be traced back to key figures like Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836–1920), who is renowned for his discovery of helium. As the founder and first editor of the influential journal Nature, he took an avid interest in astronomical alignments in ancient buildings, even penning The Dawn of Astronomy - A Study of the Temple Worship and Mythology of the Ancient Egyptians (1894)4, one of the earliest archaeoastronomical works.

When discussing archaeoastronomy, it is impossible to overlook the Giza pyramid complex—an iconic example of ancient constructions that reflect a deep understanding of celestial bodies. The pyramids mirror a non-zodiacal star constellation, and there’s a statue known as the Sphinx, bearing a striking resemblance to Leo—the fifth astrological sign of the Zodiac, possibly denoting the Age of Leo. The Pyramid of Khufu is of particular interest because of its ability to mark the day of an equinox. This feature is a testament to the extraordinary craftsmanship and scientific sophistication of the civilization that built it.

The Pyramid of Khufu, also known as the Great Pyramid, has a unique eight-sided structure, rather than the four sides typically associated with pyramids. This design enables the sun’s light to mark the construction when the light comes from a direct, perpendicular direction towards a given side of the pyramid. Considering the Pyramid of Khufu’s precise alignment with the North, there are only two days in a year—the equinoctial days—when the pyramid can be marked as seemingly intended.

A fascinating insight into the unusual design of the Great Pyramid comes from J.P. Lepre’s comprehensive work, The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference (1990)5:

One very unusual feature of the Great Pyramid is a concavity of the core that makes the monument an eight-sided figure, rather than four-sided like every other Egyptian pyramid. That is to say, that its four sides are hollowed in or indented along their central lines, from base to peak. This concavity divides each of the apparent four sides in half, creating a very special and unusual eight-sided pyramid; and it is executed to such an extraordinary degree of precision as to enter the realm of the uncanny…

The Great Pyramid was clearly designed and built with astronomical knowledge in mind, indicating equinoctial sunrises and sunsets and marking the progression of the precession6. Furthermore, there is evidence of Zodiac symbolism within the Giza pyramid complex. The Sphinx, a lion-like figure, faces due East, directly towards the rising Sun on equinoctial days. This position implies the Sphinx looks at the Zodiacal constellation hiding behind the Sun at these precise moments—does this mean it is a nod to the Zodiac sign Leo?

While this interpretation may seem conjectural, the more we learn about these ancient civilizations and their understanding of the cosmos, the more plausible it becomes. The law of Occam’s razor—that entities should not be multiplied without necessity—suggests that the more congruent factors we find in the construction of these monumental buildings, the more likely it is that this highly sophisticated astronomical knowledge has been applied universally.

Summing It Up

The Great Year and its Twelve Houses have intriguing aspects that tie in closely with the Earth’s three key motions, particularly the precession. This slow westward shift of the equinoxes along the plane of the ecliptic, resulting from the precession of the Earth’s axis of rotation, causes the equinoxes to occur earlier each sidereal year. A complete precession cycle takes around 25,920 years, marking the Great Year.

This Great Year can be divided into twelve distinct months or World Ages, each lasting 2,160 years and corresponding to one of the constellations on the ecliptic, specifically a Zodiac sign. From 1950 AD, Earth and its inhabitants entered the Age of Aquarius, also referred to as the Aquarian Age or the New Age. This understanding of World Ages seems to have persisted throughout history, encoded into folklore and monumental construction, which continues to inspire awe today.

This understanding of the cosmos that’s embedded in ancient structures such as the Giza pyramids implies a civilization far advanced for its time. This notion may not conform to the traditional narrative of human progress, but it increasingly aligns with the body of knowledge unearthed through archaeoastronomy. The advanced knowledge, as demonstrated by the construction techniques, and the remarkable understanding of celestial bodies, suggest the existence of a pre-flood civilization that had mastered the art of astronomical timekeeping.

Astrological ages, as depicted in the Great Year and the Twelve Houses, provide a comprehensive chronology that has been utilized for millennia. These World Ages are not merely relics of the past, but they hold predictive power, serving as a celestial calendar of what’s to come. The progression from one astrological age to the next signifies both an astronomical shift and a sociocultural transition. Each age carries its unique character, influencing the zeitgeist and the course of human development.

It’s fascinating to consider that these civilizations, thousands of years in our past, possessed an understanding of time that we are only beginning to fully appreciate. They saw time not as linear but cyclical, marked by the celestial dance of stars and planets. It seems that they understood the inherent rhythms of the cosmos and our planet’s place within it, a wisdom that they encoded into their greatest monuments.

This glimpse into the past serves not only as a testament to the accomplishments of these ancient civilizations, but it also invites us to see the future in a new light. As we move further into the Age of Aquarius, we might find that the knowledge held by our ancestors can guide us in navigating the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. After all, the ancients viewed the cosmos not as a vast, empty space, but as a grand celestial clock, a timeless guide inscribed with the wisdom of ages past, present, and future.

The narrative presented here has been simplified for ease of understanding, but each topic warrants deeper exploration. Future write-ups will delve more deeply into each aspect, shedding more light on our ancestors’ relationship with the cosmos.

See also

Read more

Merriam-Webster is a reputable and widely recognized American publisher known for producing dictionaries and reference books. According to their definition, precession refers to the slow gyration of a spinning body’s rotation axis around another intersecting line, creating a cone-like motion. It is characterized by a gradual rotation that forms a cone shape over time. See here for more: precession (noun) | Merriam-Webster ↩︎

The precession of the equinoxes refers to the cyclic motion of the equinox points along Earth’s orbital plane caused by the gradual shift in Earth’s axis of rotation, as explained by Britannica, a renowned and authoritative encyclopedia publisher that provides comprehensive and reliable information on a wide range of subjects. See here for more: precession of the equinoxes | Britannica ↩︎

According to Merriam-Webster, the term zodiac has the following definitions: a) Zodiac refers to an imaginary band in the celestial sphere that is centered on the ecliptic, encompassing the apparent paths of all the planets. It is divided into 12 constellations or signs, with each sign considered to extend 30 degrees of longitude, and is commonly used in astrology. b) Zodiac can also refer to a figure that represents the signs of the zodiac and their corresponding symbols, often used in astrological charts or illustrations. See here for more: zodiac | Merriam Webster ↩︎

The Dawn of Astronomy - A Study of the Temple Worship and Mythology of the Ancient Egyptians (1894) ↩︎

J.P. Lepre: The Egyptian Pyramids: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference (1990) ↩︎